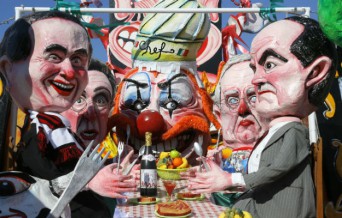

Even by Italian standards, the 2013 election -- taking place Feb. 24 and 25 -- has proved to be a weird one.

In January, former Italian prime minister and current candidate Silvio Berlusconi praised Benito Mussolini, Italy's dictator for some 20 years, saying that the racial laws of 1938, which barred Jews from universities and many jobs, "are the worst fault of Mussolini, who, in so many other aspects, did good." A few days later, Berlusconi questioned a young woman in front of a laughing crowd, asking, "Do you come? Only once? How many times do you come? With what sort of time intervals?"

Berlusconi's competitor Beppe Grillo, the comedian turned populist insurgent who's now enjoying up to 20 percent support, invited al Qaeda to bomb the Italian Parliament, flirted with neo-fascist groups, and chased public-television cameramen away from his meetings.

Meanwhile, Oscar Giannino, a former Republican turned leader of the new party, Fermare il Declino, had to abruptly quit his race when University of Chicago Booth School of Business professor Luigi Zingales, one of the party's founders, announced that Giannino's CV was a fabrication. Giannino falsely claimed that he got a master's degree in Chicago and a law degree in Rome. He even made up that, as a child, he had sung in the popular TV show Zecchino d'Oro.

Of course, many voters have come to expect this sort of thing out of Berlusconi, Grillo, and the colorful Giannino. More surprising has been the behavior of the incumbent. As a distinguished economist, college professor, and former European Union commissioner, Mario Monti once looked like what we really needed: an aloof gentleman, conservatively dressed, businesslike, soft spoken. Well, the political bug bit Monti badly. He toyed with a puppy on live television and publicly adopted him, even if the show had only rented the hapless dog from a kennel. Convinced that social media is the highway to contemporary politics, the once-detached Monti started his own Twitter account, @SenatoreMonti, surprising everybody with a barrage of teenagerish "WOW :) :)."

Given this behavior, it's not that surprising that Pier Luigi Bersani, leader of the center-left Democratic Party, still enjoys a lead before the polls open on Feb. 24. He has avoided big missteps, running a very low-key campaign. In the early stages of the race, when Berlusconi and Monti together accounted for more than 120 hours of on-air news coverage, Bersani decided to reduce his own TV presence to just 20 hours. A few voices dissented among his staff, but he did not relent.

The pollsters agree that Bersani should get a clear majority in the Chamber of Deputies, the lower house of Parliament. However, he is still fighting to get control of the Senate, which he needs in order to become prime minister. But a byzantine electoral law, devised in 2005 by Berlusconi's cronies to weaken stable cabinets, leaves all scenarios open. And as he has throughout his career, Berlusconi has bounced back, thanks to his knack for electoral promises. This year, he has proposed to scrap the unpopular real estate tax that Monti recently passed, conveniently ignoring the fact that his own party voted for it. That was then, this is now, and now Berlusconi needs votes; he's polling at around 25 percent. Votes aside, it would be impossible for most Italian cities to square their budgets without the tax -- and markets would be nervous if Italy were to yet again take the path of fiscal recklessness. The worst days of the eurocrisis seem to have ended with more than 100 billion euros in foreign investments recently returning to Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain. This is money the job market badly needs, but it may soon run out if the election aftermath is messy.

Given the state of the electorate today, it's likely to be that way. Have a look at the charts produced by Tychobigdata, a big-data start-up linked to the IMT Institute for Advanced Studies in Lucca: When Berlusconi launched his campaign against the tax, the conversation on Twitter focused on him, adding to the traditional media advantage that he, as owner of three television networks, has traditionally enjoyed. The fact that there were just as many tweets and Facebook postings blasting Berlusconi didn't matter. Once more, he dictated the Italian political conversation, controlling the dominant issues. But the regional charts show just how intense the political conversation is within the different areas of the country. Bersani is still working to be recognized as a political leader in the south; Monti is strong in Rome and the north, but he lacks a consistent base. Both Berlusconi and Grillo, however, appear as true national leaders, discussed all over Italy on the web.

Bersani's likely plan is to muster a majority in the Chamber of Deputies and -- should he fail to secure one in the Senate -- to propose a pact with Monti and his centrist allies. In private conversations, Bersani confirms he will propose the pact even if he has an overall majority. He acknowledges the Italian fiscal crisis is not over; analysts say that more than 13 billion euros may be needed to balance the budget in 2013. He also knows that Italy's powerful unions will protest any further public-spending cuts and that he needs the centrists to tame them.

At the same time, raising the fiscal pressure on taxes, which are already heavy -- at around a 46 percent rate for top-bracket individuals and businesses -- would kill growth. A moderate reformist, Bersani looks at French President François Hollande's political fate with apprehension: Hollande has failed so far to implement his electoral promises, and it took a military intervention in Mali to improve his approval ratings. Bersani does not have a military "wag-the-dog" option. He sees a slow course of reforms, focusing on jobs, the south, and boosting private consumption -- yet he will be resistant to any spending sprees. Not long ago, Europe's economic basket cases were the PIIGS: Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, and Spain. Now, in Europe, everybody worries about FISH -- France, Italy, Spain, and Holland -- the fear being that these economies will be crippled by high-spending Socialist governments.

The wildcard is Grillo. He's hoping for a weak cabinet, forcing a national unity pact of Bersani, Monti, and Berlusconi, which would leave him as the sole leader of the opposition. How will Grillo lead his troops -- all of them political debutants? In Sicily, where his 5 Stelle party now exercises power after local elections last fall, he has been mostly a naysayer. 5 Stelle successfully blocked the stationing of MUOS, a U.S. satellite system that would protect NATO's southeast flank in the Mediterranean and serve as a strategic asset in Syria -- over vague health concerns. He talks of Italy withdrawing from the eurozone, renegotiating all international agreements, and calling home troops from most peacekeeping missions. This could be political posture, but 5 Stelle is unpredictable. More than 100 of his Grillinis are expected to enter the Chamber of Deputies and Senate after the upcoming elections. The moderate left is already, cautiously, checking them out, hoping a few of them -- tired of Grillo's tirades -- will later join arms.

Should the election results match the latest polls, Italy's political dilemmas may not be over for a while. Bersani, even as a prime minister, should ponder why his Democratic Party is still failing to entice the middle-class vote in the productive, high-tech north. Monti should find a new, more nuanced balance between being a technocrat and a politician. Berlusconi has to decide what to do with the 25 percent of the votes he'll get -- play the spoiler or eventually find a true political heir? Even Grillo, after the raucous celebrations of his "Grillini" are over, will discover that running the world's sixth-largest economy and Europe's second industrial power is, after all, no laughing matter.